[ad_1]

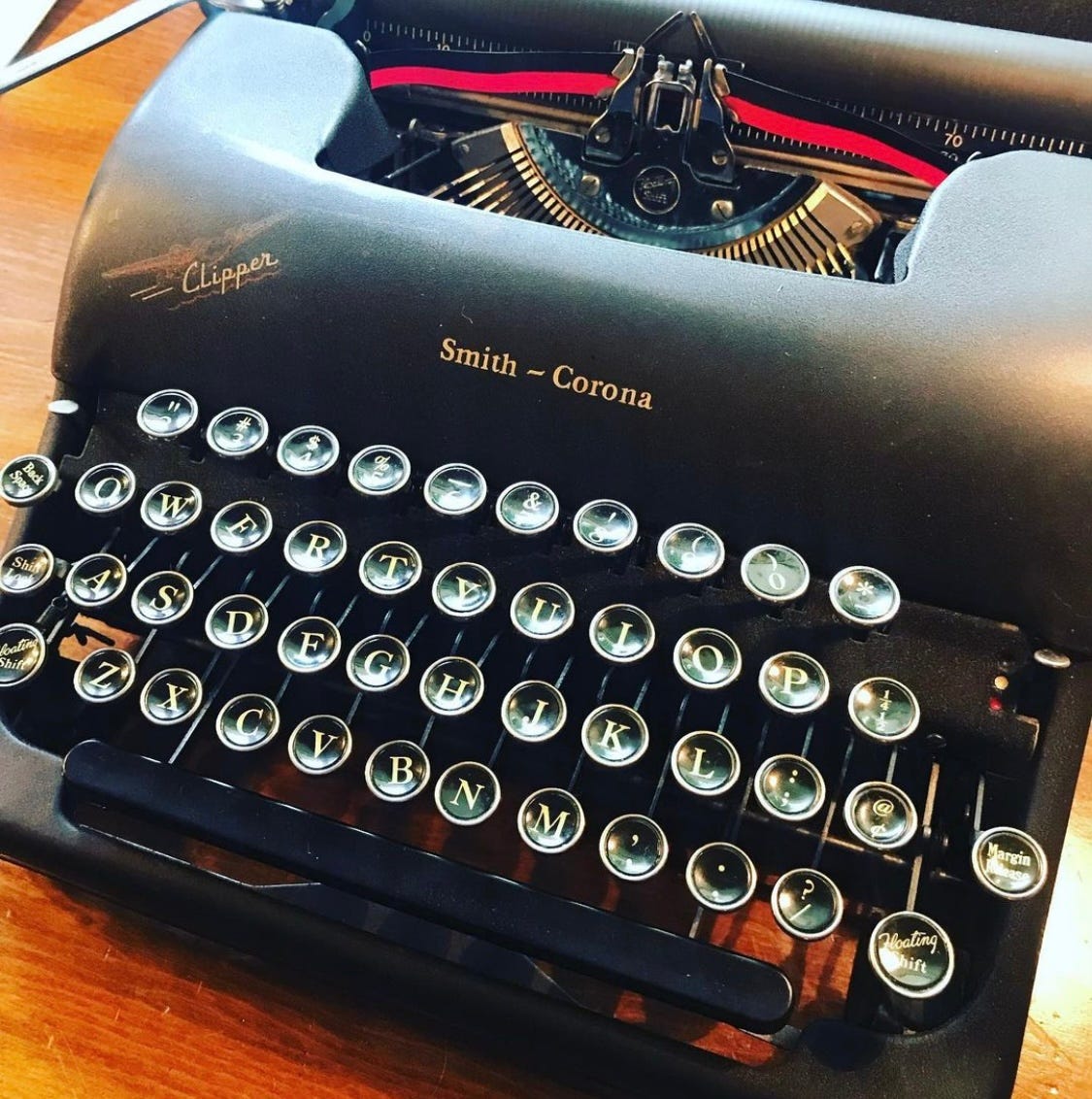

It’s rare these days to see anyone pounding away on an old manual Royal or Smith-Corona.

But one element of those machines lives on, and is used constantly in daily life.

Just as Milwaukee is the birthplace of the typewriter, it’s also the birthplace of the QWERTY keyboard, both of which are turning 150 years old.

Milwaukee will mark the inventions with QWERTYFEST, a weekendlong celebration.

The first typewriter was patented in 1868 and resembled a miniature piano with two rows of white and black wooden keys. It was the invention of Christopher Latham Sholes, Samuel Soule, and Carlos Glidden. Over time, Sholes tweaked the design by rearranging letters, adding a few rows, and making the keyboard narrower.

Since 1873, when the first typewriter was commercially produced by Remington Arms Company, the QWERTY keyboard has essentially remained unchanged. Take a look at your own laptop keyboard. Numbers sit in the top row. Punctuation marks are grouped together on the right-hand side. Letters are arranged in a seemingly random fashion underneath the numbers. QWERTY refers to the first six letters on the upper left.

That was all Sholes’ doing.

Why are the keys arranged this way?

The popular theory is that the letters were scrambled, rather than organized alphabetically, to intentionally slow down users and force them to use a “hunt and peck” method, in which typists must scan the keyboard before pressing the correct keys. That forced them to slow down and helped prevent the keys’ thin metal bars, or typebars, from jamming together.

Jason Puskar, an English professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, challenged that notion.

“How long would it take you to learn the new order?” he said. “If you’re a typist, scrambling the keys is not a solution that’s going to slow down typing for very long.”

Puskar argued that in some ways, QWERTY was designed to actually speed up typing. Consider the placement of “T” and “H.” “TH” is one of the most common two letter combinations in the English language, and these keys are directly diagonal from one another on the keyboard. That would seem to invite a jamming problem.

However, inside those typewriters, character typebars were arranged in a 360-degree basket. When a key was pressed, the typebar extended, struck an inked ribbon, and made an imprint of the character on paper before returning to its resting position. Although “T” and “H” are close on a keyboard, their typebars were 180 degrees apart, as far away from one another as possible, preventing any chance of key jamming.

That kind of optimization was not always consistent. For example, “E” and “R”, another common combination in English, are next to one another, but their typebars are only 16 degrees apart and could easily collide.

“Some of (the letters) seem to be laid out just right, but others, not so much,” said Puskar. “At some point, you have to get the letters on there, and you’re going to have to make some compromises.”

Additionally, the letters on the QWERTY keyboard are arranged somewhat alphabetically, with a few exceptions, and resemble the layout of early printing telegraphs. The telegraphs had two rows of black and white keys like a piano keyboard. The black keys listed A-M, going from left to right, and the lower, white keys went from N-Z, right to left.The QWERTY keyboard is similar. Its middle, home row, for example, starts with A on the left, and if you remove S and the other vowels, the keys are arranged in loose alphabetical order.

“That’s not very scrambled,” said Puskar.

The keyboard design doesn’t really make sense

QWERTY quickly became the universal, standard keyboard, though critics have pointed out it has several flaws in its design:

- It’s left-hand dominant. For English speakers, about 57% of keystrokes are made with the left hand, even though most people are right-handed.

- Some fingers are disproportionately used. For example, the shortest finger, the pinky, is overworked and forced to stretch long distances. It manages letters, numbers, punctuation marks, shift keys, tab, and the return/enter key. “One of my biggest issues is that some of the letters that you use the most … the ‘A’, for example, (uses) your left pinky, and I’m right-handed,” said Lisa Floading, an avid typewriter collector. “My left pinky is probably the least strong of all of my digits, and so when I’m typing that letter, it doesn’t always show up as it should.” In contrast, the longest, middle finger is comparatively underworked.

- Very little typing is done on the home row where our fingers rest. Many words require us to jump back and forth between rows, which takes up time.

Alternative keyboards have been designed over the years that circumvent these issues and are, arguably, more efficient. Those include the Dvorak (1936), Colemak (2006), Workman (2010), and KALQ (2013). None of these keyboards took hold.

Why not? Why, given that we’re no longer attached to the physical limitations of the original key-and-ink typewriters, do we cling to the QWERTY design?

Puskar called it the “million-dollar question.” Once something is institutionalized, he suggested, it’s hard to break.

“It’s similar to driving on the left or right side of the road. It would be more efficient (for England) to use the same cars as everybody else, but the overhead to do that and the (pushback) you would get from people would be too much,” explained Puskar.

Most, if not all, of us were trained to type on a QWERTY keyboard. It’s ingrained in our spatial and muscle memory.

QWERTYFEST will celebrate a piece of Milwaukee history.

Efficient or not, QWERTY remains the universal, standard keyboard, and after 150 years, that’s worth celebrating — at least to aficionados in its hometown.

“It touches on Milwaukee history and recognizes all of the cool things that are happening in this city,” said Floading.

Puskar went further, calling it “Milwaukee’s most impressive contribution to the entire globe.”

It took over the world, he said, “and nobody knows it’s from here.”

[ad_2]

Source link